Here are some Christmas greeting ads from the Alleghany News files archived at DigitalNC:

See all the Alleghany News files in the archive, here.

Here are some Christmas greeting ads from the Alleghany News files archived at DigitalNC:

See all the Alleghany News files in the archive, here.

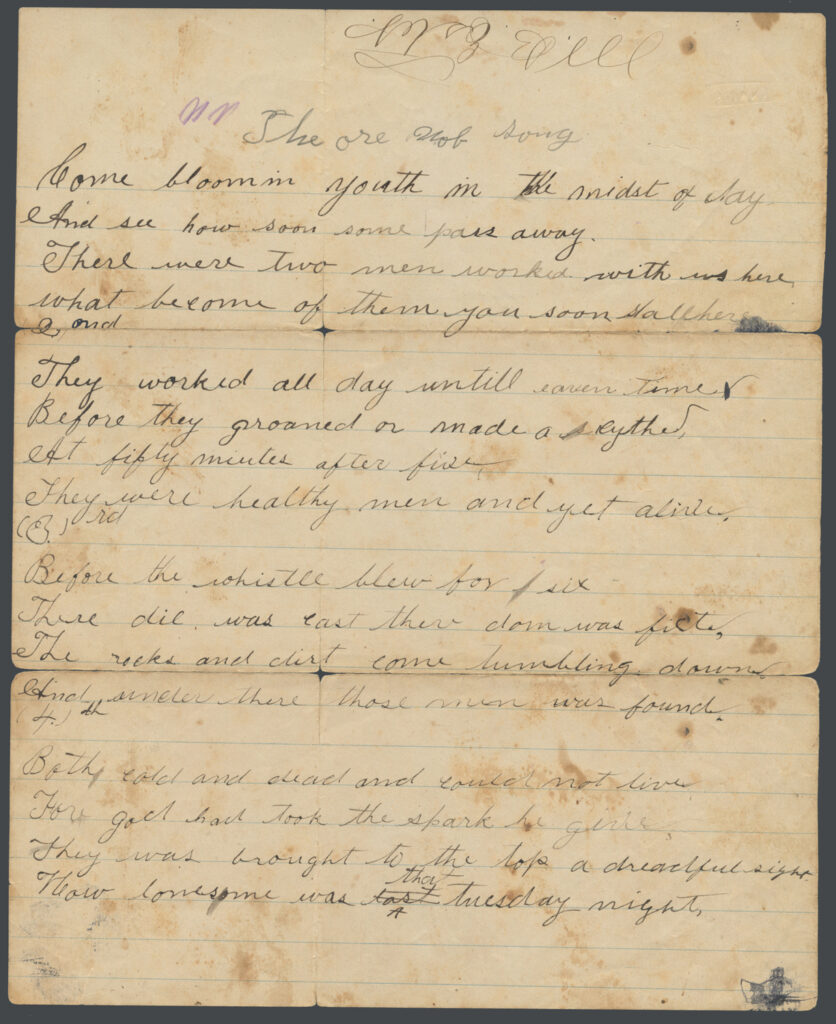

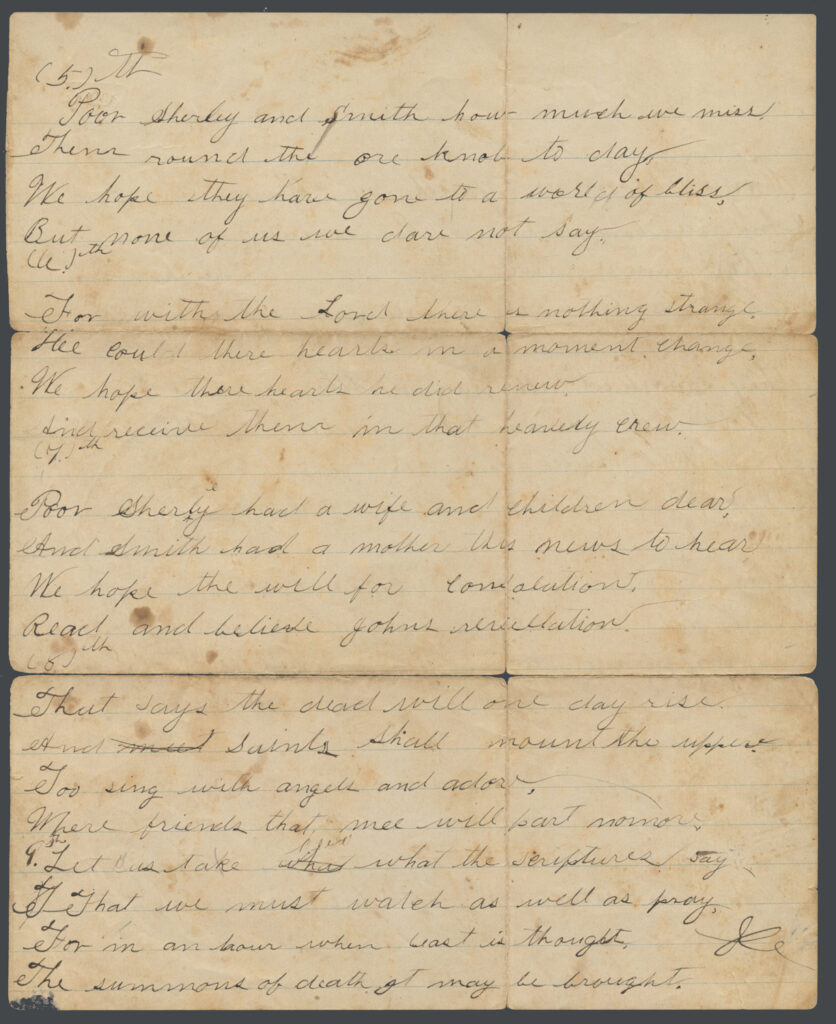

Here is one of the newest additions to the Alleghany Historical Museum. It’s a single page (now in three parts due to its age) bearing a handwritten song lyric that fills both sides of the sheet. It is undated and unsigned except for the name W.B. Estep, which is written, upside-down, at the top of side one.

I say “unsigned,” because, although Mr. Estep might have written it, I don’t think he was the author. Wilborn Berry Estep (1874-1941) lived at Whitehead, North Carolina. His granddaughter was Irene Richardson Wagner. Irene was a charter member of the Alleghany Historical – Genealogical Society, and she passed away in 2019. Her son, Ross Wagner, donated his great-grandfather’s manuscript to the museum.

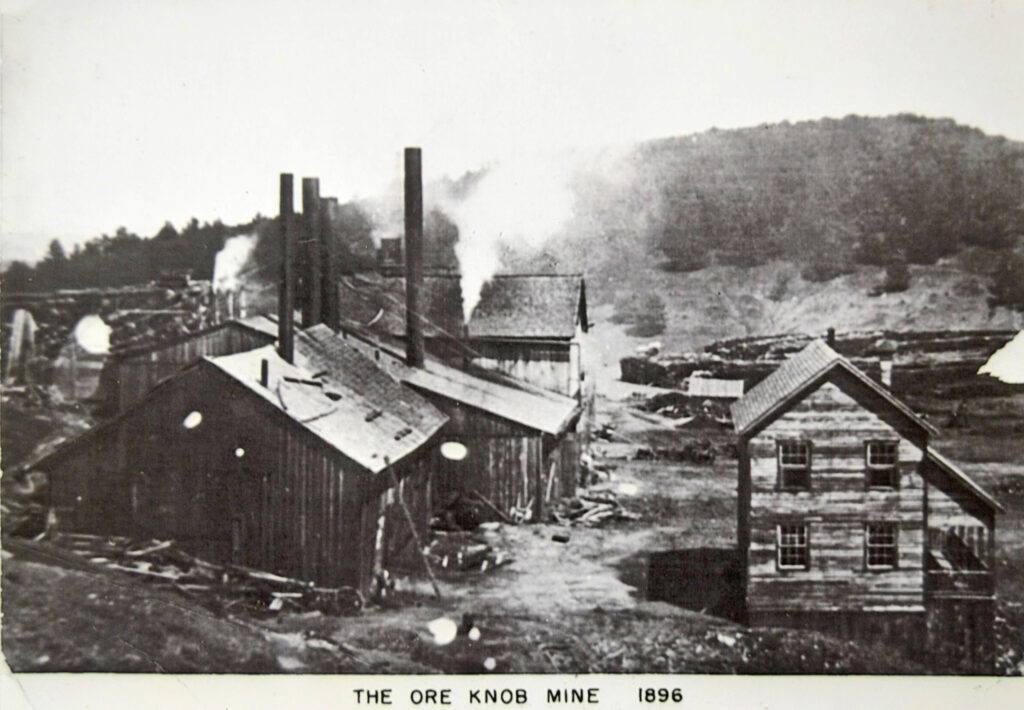

The song is called “The Ore Nob Song” and tells the story of a cave-in at the Ore Knob Copper Mine in neighboring Ashe County in the 1800s. The event was tragic in that two men were killed and two others were injured. We had heard of the song. Somewhere along the way, I’d seen a transcript. It mentions the surnames of the two men who lost their lives, Smith and Sherly, but it gives no dates or any other personal info, except that Sherly had a family and Smith was unmarried and lived with his mother.

So I started looking. I thought it would be a snap. A story like this would have made the papers. And I’d easily find the men on genealogy apps. But it wasn’t so easy.

Initially, I found two versions of the music and several variations of the lyrics in the Special Collections Research Center archive at Appalachian State. The lyrics closely matched what Mr. Estep had written down. But there were no dates on any of the documents. And no songwriter was listed. Except for the name Chas. Liddle at the end of one of the sheets along with a second, unintelligible name.

I also found a listing in an archive at Middle Tennessee State University, for another lyric manuscript called “The Oar Knob Song.” But I couldn’t see the actual file. It looks like it is only available at archive.org and that site is temporarily (I hope) inaccessible.

In the description of the MTSU document, however, it said:

1 sheet with handwritten lyrics…

Inscription beneath the lyrics reads: “Rote June the 27 : 1879, James M. Wilson”.

Inscription on the back of the page reads: “Bettie Calloway, Old Town Grayson Co., Va”.

Most likely a reference to Ore Knob Mine in Ashe County, North Carolina.

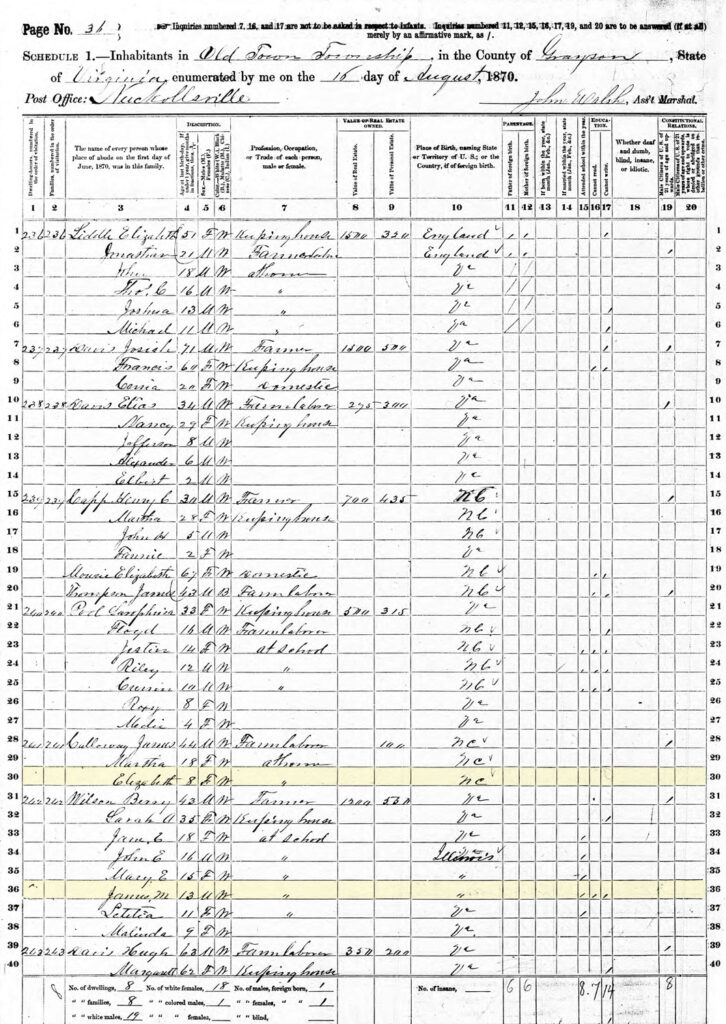

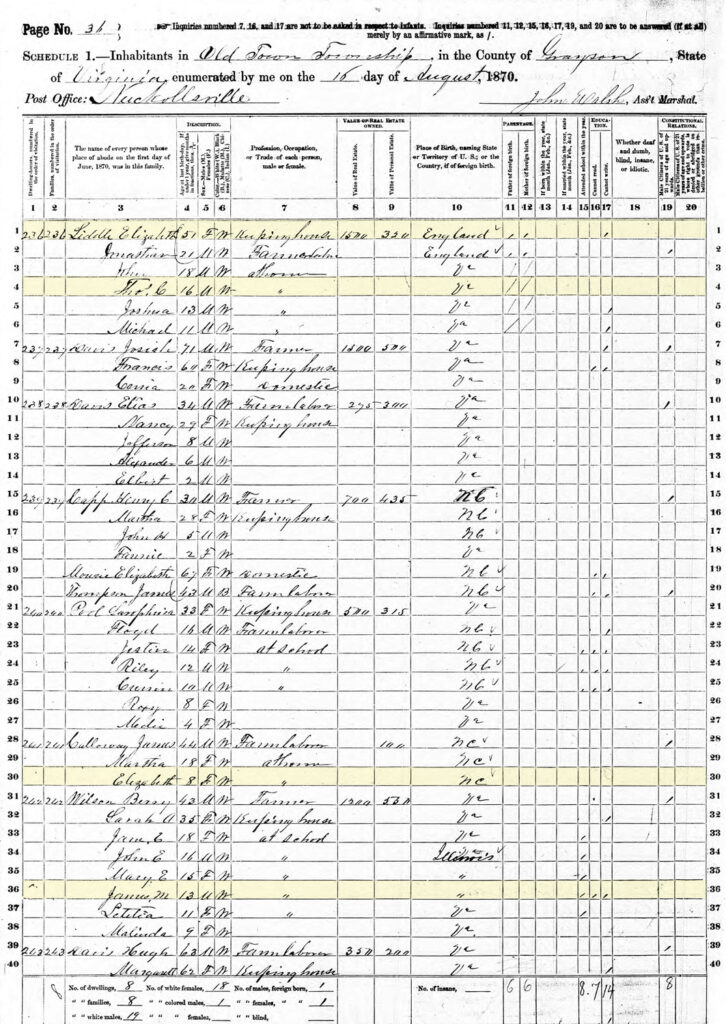

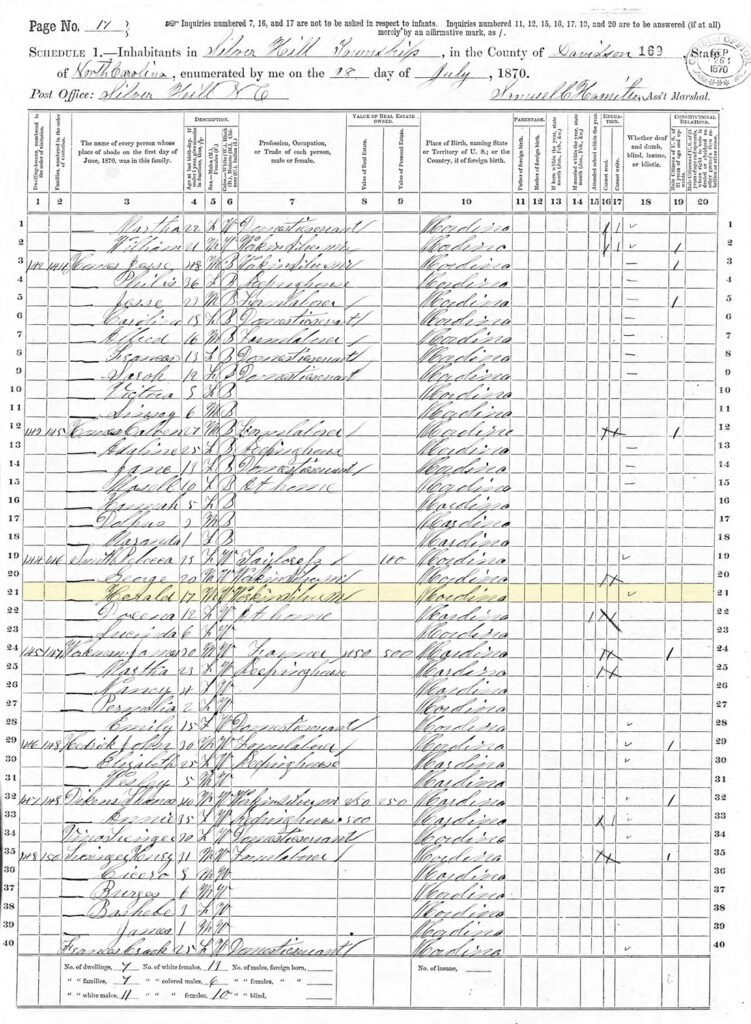

So I looked and was able to find both names from that document, “James M. Wilson” and “Bettie Calloway” in the 1870 census living next door to each other, at Old Town in Grayson Co. Virginia. James (Madison) Wilson was 13-years-old in 1870 making him 22 if/when he wrote the page and Elizabeth “Bettie” was 8, so 17 or so in 1879. (They’re also both listed in the 1880 census, still in Old Town, but they weren’t close neighbors any more.)

On the same page of the 1870 census, there is a family headed by Elizabeth “Betsy” (Wilson) Liddle. She had a son named Thos. C. Liddle (remember, one of the ASU sheets is signed Chas. Liddle.)

It’s conceivable that men from Grayson County were working at the mine in Ashe at the time of the accident and Miss Calloway, the Wilson’s and the Liddle’s might have all been involved in the writing of the song.

This, of course, is conjecture. I’d welcome someone’s help with actual facts.

Now, about Sherly and Smith. I went straight to the horse’s mouth on this one- the Ashe County Historical Society’s blog and an excellent article on the history of the Ore Knob Copper Mine by our friend, Josh Beckworth.

…the community that developed around the copper mine was surprisingly populated. In 1880, the entire county of Ashe had a population of 14,447 people, approximately 28 people per square mile. However, the one mile square area around the Ore Knob mine recorded nearly 500 residents. These residents formed a well developed community that included a hall for dances, a church, and numerous stores.

…this booming community became a powerhouse of copper extraction. In fact, it was for a time, one of the largest copper mines operating in the United States. Millions of pounds of ore was extracted, sorted, and smelted through a variety of processes. In 1879, the mine was reported as producing 90 tons of copper ore per day.

www.ashehistoricalsociety.org

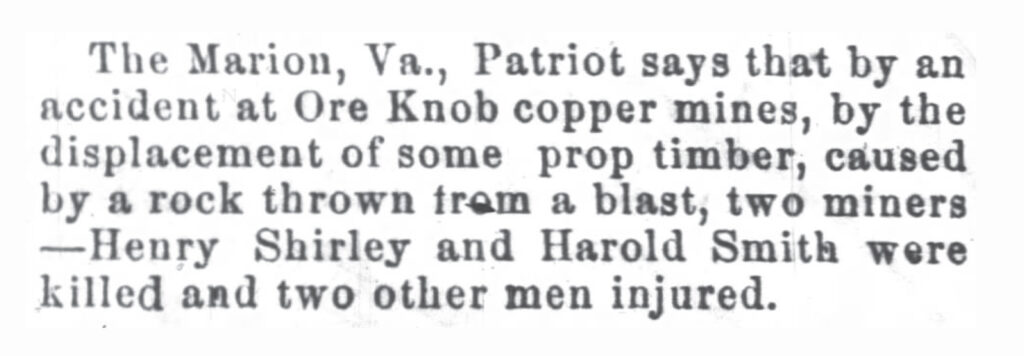

Josh had helpfully included a newspaper clipping, there, that listed the men’s given names: Henry Shirley and Harold Smith and a date for the tragic event: 1876. That date fit with the MTSU document of 1879.

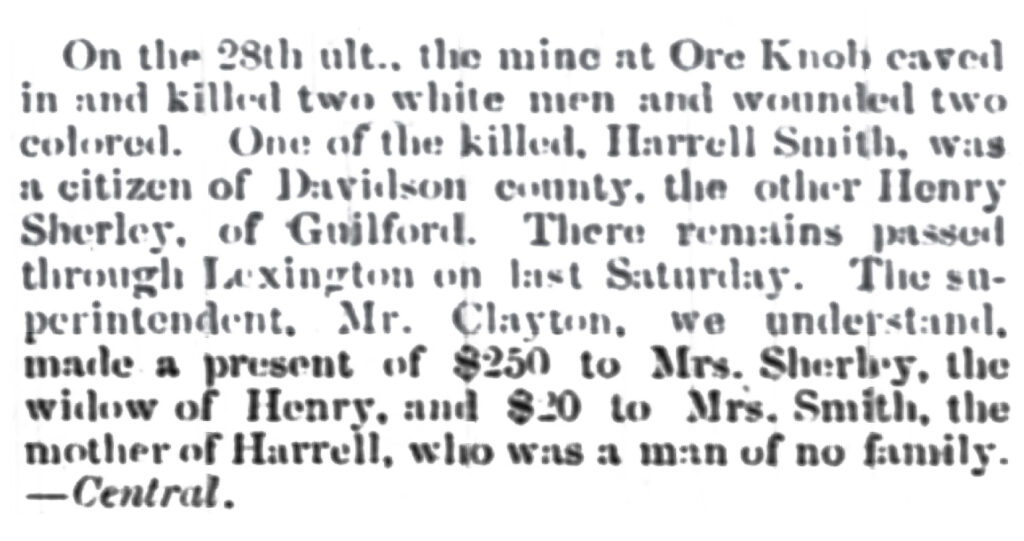

I asked Josh if he had other info on the accident at Ore Knob. He let us know that his original clipping came from the April 13, 1876, edition of the Goldsboro Messenger. He also sent us a second article— this one (with the same date, but from the People’s Press of Winston-Salem) told where the men came from. Harrell Smith was from Davidson County and Henry Sherley was from Guilford.

The article also gave a firm date for the event- March 28, 1876.

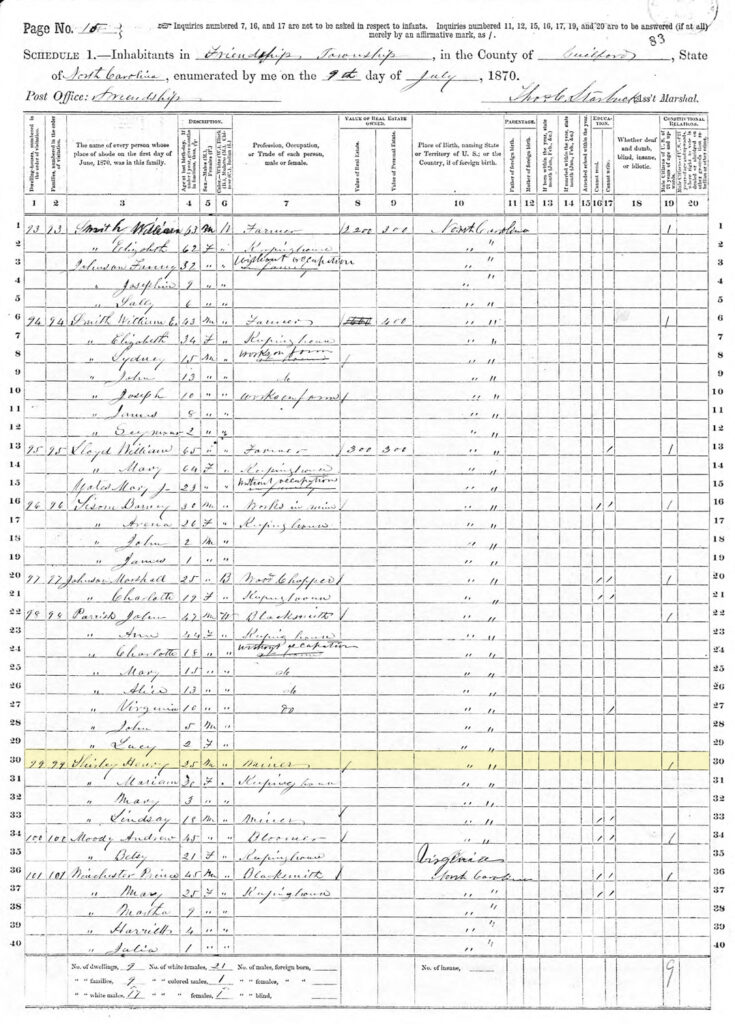

With this information, we were able to find in the 1870 census:

Herald Smith of Silver Hill in Davidson County, NC. Herald’s occupation, entered there, “Work in Silver M.” Production at the Silver Hill Mine in Davidson (the first silver mine in the United States) began in 1839 but had dropped off in the 1870s and it was mostly shut down by 1882. It makes sense that a young man like Herald- 23 in 1876- might travel to “one of the largest communities in Ashe County at the time,” for work in which he was already experienced.

We also found:

Henry W. Shirley of Friendship in Guilford County, North Carolina, who would have been 31 in 1876, was married to Mariam Becknell Shirley. They had 2 children and his occupation is listed in the 1870 census as “miner.”

Neither Herald Smith, nor Henry W. Shirley are listed in the 1880 census.

(Variation from the Estep Family of Whitehead, NC)

Come bloomin youth in the midst of day,

And see how soon some pass away.

There were two men worked with us here,

What become of them you soon shall here.

They worked all day till even time,

Before they groaned, or made a scythe.

At fifty minutes after five

They were healthy men, and yet alive.

Before the whistle blew for six,

There die was cast, there dom was ficts.

The rocks and dirt came tumbling down,

And under there those men were found.

Both cold and dead,and could not live,

For God had took the spark he give.

They was brought to the top, a dreadful sight,

How lonesome was that Tuesday night.

Poor Sherly and Smith! how much we miss

Them round the Ore Knob today!

We hope they have gone to a world of bliss

But none of us we dare not say.

For with the Lord there is nothing strange,

He could their hearts in a moment change.

We hope there hearts He did renew,

And receive them in that heavenly crew.

Poor Sherly had a wife and children, dear,

And Smith, a Mother, this news to hear.

We hope the[y] will for consolation

Read and believe in Johns revelation,

That says the dead will one day rise,

And saints shall mount the upper [skies?],

Too sing,with angels and adore,

Where friends that mee[t] will part no more.

Let us take heed what the scriptures say

That we must watch as well as pray,

For in an hour when least is thought,

The summons of death, it may be brought.

You can hear a beautiful rendition of the song, performed by Mary Jane Miller at the 43rd Annual Old Fiddlers Convention (at Galax in 1978), here

[07:18] A5 – The Ore Knob [Mary Jane Miller]

AHGS hopes this little bit of history will help to highlight the tremendous danger of extreme weather that will sometimes even reach the Blue Ridge. We continue to pray for everyone who has been affected by this terrible storm, that they are comforted and healed and housed and clothed, as soon as possible.

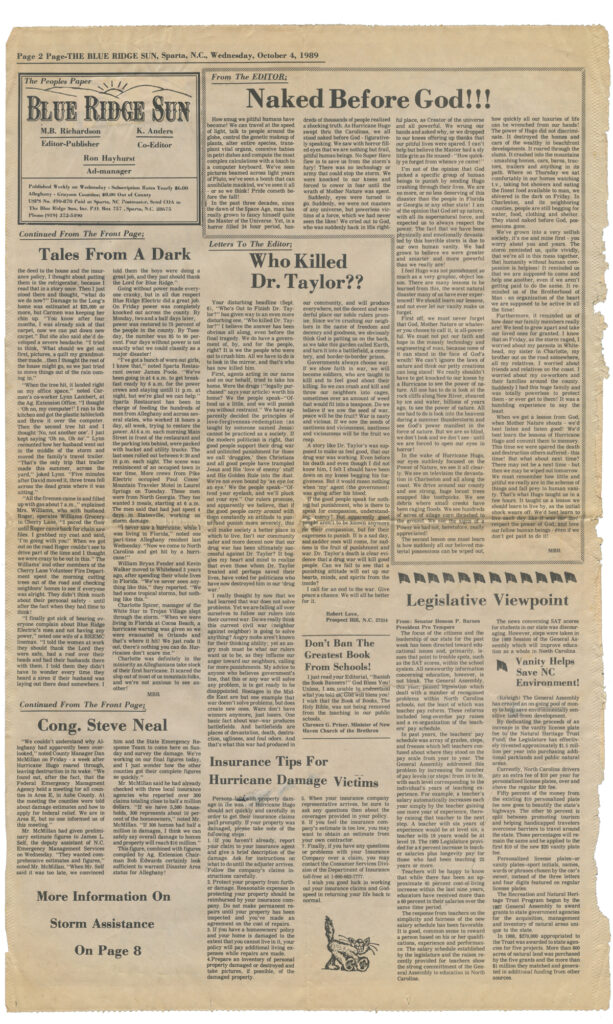

Hurricane Helene hit Alleghany head on, almost exactly 35 years after Hugo’s disastrous visit. Here are the first two pages of the Blue Ridge Sun from 35 years ago, today.

From the September 28, 1989 edition of the Alleghany News:

Calling Hugo the “worst natural disaster to hit Alleghany County,” Chairman of the Board of Commissioners Kenneth Richardson estimated the damage to the county could total $32.5 million or more after the full impact on agriculture, roads, buildings and summer homes is assessed. Richardson said he believed 10 percent of the county’s $325 million tax base had been damaged in a Monday morning press conference at the County Office Building. He also called attention to a CNN news report that said Alleghany may be “the most severely damaged county in North Carolina.”

Early reports of insurance claims indicates Alleghany is running ahead of the more populated counties of Wilkes and Ashe. DSS Director Sandra Ashley said 30 people had sought shelter in the evacuation center set up at AHS. She praised the Dollar Mart for donating sandwiches for them to eat. David Osborne, Rescue Squad Captain, estimated that their 30 squad members had volunteered from 900 to 1,000 hours since the storm.

Also praised were the efforts of all local fire departments, highway patrol, deputies and police. The hardest hit by the storm is probably local agriculture, particularly dairy farmers. Extension Director Bob Edwards estimated a $1 to 2 million loss for the 3,500 to 4,000 acres in corn for silage.

Edwards said that 23 of the county’s 75 dairies were without electricity Saturday afternoon. He estimated that 20 percent of the dairy cattle that went 24 hours or more without milking would develop mastitis and 10 percent would eventually have to be culled. Monday, only two dairies were without power and both were being milked with National Guard supplied generators. He estimated agricultural damage at $8 to 10 million.

BREMCO District Manager Russell Sheets estimated damage throughout the cooperative at $1.5 million. He reported 1,500 homes were still without power. He hoped all the county would have power by Thursday. That date was later revised to the weekend as linemen continued to find more damage than first expected.

Walt McMillan, manager of Sparta’s Skyline Telephone office estimated only 80 of their 4,200 customers were without service, down from a high of about 500 Saturday. He explained that phone lines fared better because they were somewhat protected by power lines which broke the impact of trees and debris.

THANK YOU to our sponsors, our volunteers and everyone who helped support the Saturday Afternoon Social! This year’s event raised over $5500 for the Museum.

We would ask that you patronize these businesses who give generously to benefit the Historical Museum. Without this community support, the Museum wouldn’t exist.

While the Blue Ridge Parkway might seem like any other road in the high country— roads that evolved from ancient, native American trails— it is, arguably, anything but.

The 469-mile long “Scenic” as it was called at the beginning, here in Alleghany, might possibly be the most designed, discussed and disputed drive ever to be constructed in America.

The parkway was first proposed in the 1930s to connect the new National Parks at Mammoth Cave, Kentucky; the Shenandoah in Virginia; and the Great Smoky Mountains National Park in Tennessee & North Carolina, but Kentucky was dropped from the plan at some point.

New Deal funding was approved by the Public Works Administration in November of 1933 for this “national parkway” that would connect two national parks.

We, who live equidistant to both parks— the midpoint of the parkway is right here in the county— might think of the Parkway’s location as obvious. Questioning it would be as absurd as that of the sites of the New River or Stone Mountain or the Sphinx.

But, let’s consider time before our beloved road… before any blasting or grading began; before the building of the bridges, the overlooks, the fences or the trails; before the meticulous landscaping— down to the installation of individual trees and shrubs (!)— even before any land was acquired, a route had to be determined and decided upon.

This formidable dilemma was to be resolved only at the highest levels of the federal government.

From the beginning, the route through Virginia was reasonably undisputed, but by early 1934, Tennessee and North Carolina had already initiated what would become a contentious battle for the southern half of the parkway.

Tennessee wanted it to veer to the west, near Lexington, Virginia, continue to Damascus, then head south to Unicoi, Tennessee, and finally on to Gatlinburg— Tennessee’s “western gateway” to the Smokies.

North Carolina, however, wanted it to follow the path that essentially exists, today.

While politics surely influenced the final decision of Secretary of the Interior Harold Ickes (and Franklin Roosevelt. Conventional wisdom says Bob Doughton, powerful chairman of the House Ways and Means Committee, privately agreed to support the Social Security Act if Mr. Roosevelt gave NC the parkway) the very public battle for the parkway was one of oratory— a noble debate of economics and engineering and, of all the intangible and subjective things, “scenic beauty.”

© 2025 ahgs.org

Theme by Anders Noren — Up ↑